JULIET ATELLAH – Surviving Hunger – Kenyans Forced to Cope With Increased Food Insecurity – The Elephant

Kenyans across the country are having to adjust to increased food prices as production falls due to poor rains among other causes.

Published

on

By

On 8th September 2021, the then president of Kenya, Uhuru Kenyatta, declared the drought affecting several parts of the country a national disaster. The increase in food insecurity in Kenya is mainly a result of poor rains, the COVID-19 pandemic, insecurity, as well as pests and diseases, which have led to an increase in food prices in the country.

Kenya has been experiencing a high inflation rate since the beginning of 2022. In July 2022, the overall year-on-year inflation rate as measured by the Consumer Price Index (CPI) was 8.3 per cent. This was mainly due to an increase in commodities prices in the previous 12 months, including food and non-alcoholic beverages, which on average had gone up by 15.3 per cent. The cost of a litre of cooking oil had nearly doubled to KSh359, while that of a 2-kilogramme packet of sifted maize flour, a local staple, had gone up by 14 per cent, and a kilo of Irish potatoes by 25 per cent.

A March 2022 report by the National Drought Management Authority (NDMA) estimated that by June, a quarter of the population in Kenya’s arid and semi-arid (ASAL) counties, or more than than 3.5 million people, would be acutely food insecure, with those in Marsabit, Turkana, Baringo, Wajir, Mandera, Samburu and Isiolo counties, who mostly depend on pastoralism for their livelihoods, being the most affected.

Many Kenyan households are trying to find alternatives to survive given the trends in food prices. Some in Nairobi have turned to Vibandaski—small low-cost restaurants, some sporting branded umbrellas and plastic or wooden chairs. Kamau Njoroge, who works at a construction site, says he prefers the kibandaski to cooking at home. “To make breakfast at home, I’d have to buy a packet of milk at KSh60, sugar at Ksh120, tea leaves, and a loaf of bread that is KSh60.” This is more than his daily wage of KSh200. “Compare that with the breakfast at the kibandaski which costs Ksh20,” he says.

Hellen Atieno is a trader and a small-scale farmer who has been doing business in Kisumu town for the past five years. She has a shop that stocks staple foods in the area where she buys the goods wholesale and sells them to her customers at retail prices.

Atieno narrates says that the prices of goods at the wholesaler have doubled since she started her business. “When I started my business in 2017,” she says, “I would buy 50 kilos of sugar at KSh3,000, 20 litres of cooking oil at KSh2,500 and a bundle of a dozen 2-kilogramme packets of maize flour at KSh600. Those prices have changed and currently I am buying the sugar at Ksh6,500, oil at KSh6,000 and maize at KSh1,600.”

Atieno says she has to employ different selling techniques to accommodate customers unable to afford the higher prices. For example, she used to repackage the cooking oil into 300ml soda bottles, but as prices have increased, she now also repackages into smaller quantities measured out using a stainless steel cup.

According to Atieno, many of her neighbours and customers are peasant farmers earning less than KSh200 a day from their small pieces of land. Many are forced to skip meals, surviving on only one or two meals a day. Atieno adds that poor rains have also severely reduced the produce from her farm. “I used to harvest 6 sacks of maize from my quarter-acre and right now I can only get two sacks,” she says.

The situation is worse in the ASAL counties where, according to the NDMA report, households only have stocks that can last one to two months instead of the normal three to six months as a consequence of poor rains and the cumulative effect of the previous poor seasons. “In some counties, total crop failure of maize and cowpeas was expected, as the crops wilted at germination and vegetative stages,” according to the report. Exacerbated by limited access to farm inputs and Fall Armyworm invasions, the production of these crops as well as green grams at the coast has fallen below five-year averages.

Even outside the dry counties, high food prices are expected to remain the norm, notwithstanding government efforts to introduce subsidies. In Nairobi, wholesale prices for maize and beans are anticipated to stay significantly above the five-year average levels through September. With local fuel prices expected to reflect overall high global oil prices, this signals more tough times ahead for people across the country.

–

This article is part of The Elephant Food Edition Series done in collaboration with Route to Food Initiative (RTFI). Views expressed in the article are not necessarily those of the RTFI.

The Elephant is helping to build a truly public platform, while producing consistent, quality investigations, opinions and analysis. The Elephant cannot survive and grow without your participation. Now, more than ever, it is vital for The Elephant to reach as many people as possible.

Your support helps protect The Elephant’s independence and it means we can continue keeping the democratic space free, open and robust. Every contribution, however big or small, is so valuable for our collective future.

Donate Now

Juliet Atellah is a data journalist based in Nairobi, Kenya

GMOs: Entrenching Kenya’s Food Insecurity

Food Security When Farmers and Consumers Lose Agency

Soko Mjinga: The Shamba System

Taita Taveta: The Land of Dietary Contrasts

Food Culture at the Kenyan Coast

Kericho County: Tea, Foods and Shifting Weather Patterns

Kenya is the first country in the world to have included intersex people as a distinct group during the last census in 2019. However, much remains to be done to raise public awareness across the country about who intersex people are and the importance of protecting them.

Published

on

By

John Karanja attempted suicide three times before realising that his life, after all, had meaning. Karanja, who was born Dorcas Wangui in 1993, did not notice his body was different until he was eleven years old when he began puberty. However, in order to understand Karanja’s journey, we must first understand Dorcas Wangui.

Wangui was born and raised in Gatundu South, the last of 12 siblings. The attending physician observed that the new-born possessed both female and male genitalia. He assured the parents that the child’s visible male genitalia would “disappear” as she approached puberty. The doctor was describing some of the characteristics of an intersex person.

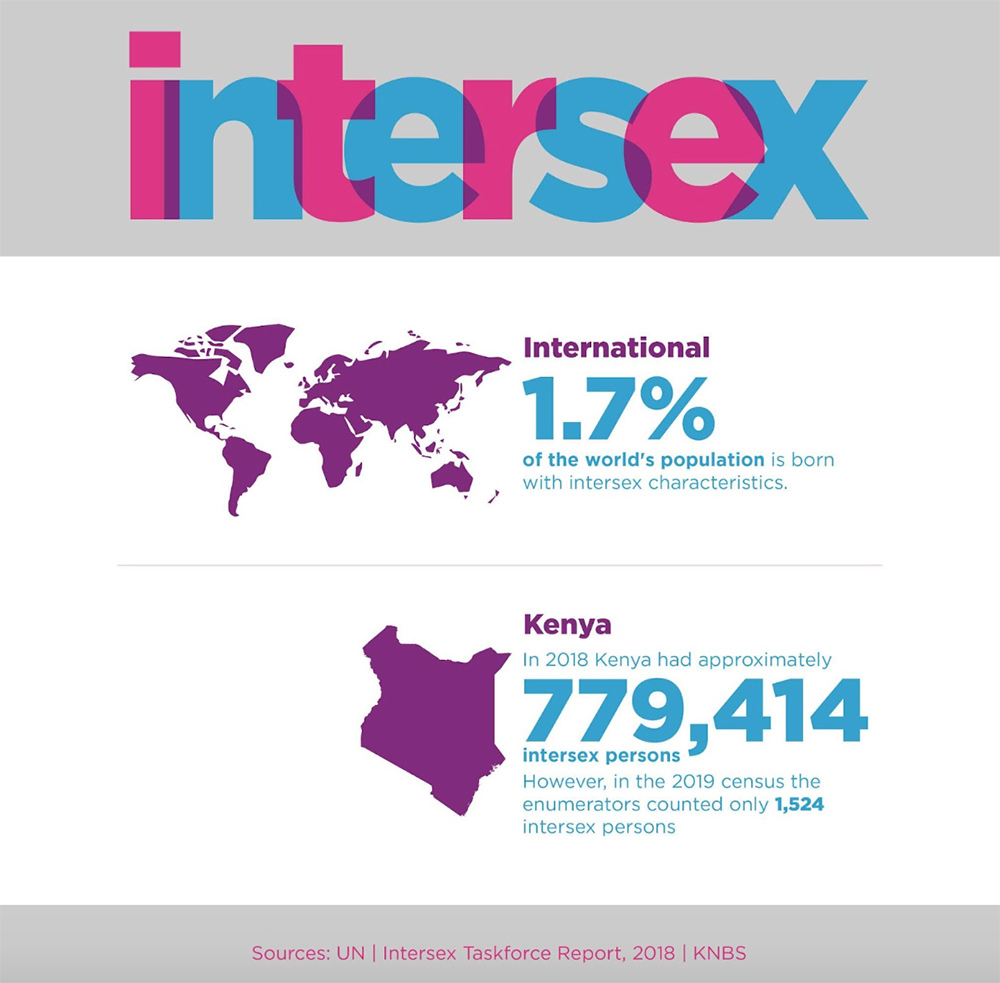

The report of the Taskforce on Policy, Legal, Institutional and Administrative Reforms on Intersex Persons in Kenya describes intersex persons as those who have ambiguous genitalia, both internal and external, and do not fit into the binary categories of male or female. The ambiguity could be anatomical (i.e. a bodily structure like the vagina, penis, or breasts), hormonal (e.g. oestrogen, testosterone), gonadal (i.e. reproductive organs like the ovaries and testes), or chromosomal (i.e. genetic makeup, e.g. XX, XY). In essence, each intersex person is one-of-a-kind. According to the UN Office of Human Rights, 1.7 per cent of the world’s population is born with intersex characteristics.

There are more than 46 variations of intersex conditions, according to Dr Milton Diamond, a renowned American professor of anatomy and reproductive biology. These variations can be detected at various stages, including pregnancy screening, birth, childhood, puberty, and adulthood; a person can have multiple variations.

Wangui’s parents returned home, overjoyed to have a daughter. They kept their worries to themselves and did not follow up with the doctor. After all, having an intersex child was and is still not openly discussed, let alone acknowledged.

Wangui’s body began to change during her adolescence, as is typical. She began to notice physical changes when she started secondary school in 2009. She was perplexed at the age of 16 as to why she had never had menstruation. Her voice was also beginning to deepen, something she only observed with her male age-mates. Wangui’s parents had never explained that she was born different from her siblings, so she had no idea how to interpret the ambiguous anatomical changes.

During this period of confusion and ridicule from peers, Wangui attempted to commit suicide but failed. She dropped out of school the following year and fled to Nairobi, leaving her family and friends in the dark.

Intersex people face discrimination from the moment they are born because they are labelled as either male or female. They face discrimination as they grow because their sex characteristics do not correspond to the gender assigned to them by medical doctors and their parents.

Consider the case of an intersex student attending an all-male school who, instead of breaking his voice, begins to develop breasts! Because there is rarely a support structure in schools—or in society in general—for intersex students, many choose to drop out. The psychological stress and pressure are enormous, and many people consider suicide as a means of escaping their situation.

Most intersex children are assumed to be female due to the biological formation of a child in the womb. Typically, the first organs to develop are female, followed by male genitalia. When a child reaches puberty, hormones begin to assign themselves in accordance with what is dominant. Intersex people have health predispositions that are uncommon in males and females, according to Dr Paul Laigong, a paediatrics endocrinology lecturer at the University of Nairobi. “These are conditions such as electrolyte imbalance, delayed puberty, infertility, sexual dysfunction (difficulty in having or enjoying sex) and gender identity crises,” he says. The latter—gender identity crisis—in particular, was what Wangui was experiencing.

Wangui was accommodated in the big city by her older sister, who lived in Kariobangi. Wangui was surprised to see so many girls and women wearing trousers, which was unusual in Gatundu, her rural home. Wangui had never worn trousers before, preferring to dress in skirts and dresses as dictated by her parents, who considered her a girl.

When a child reaches puberty, hormones begin to assign themselves in accordance with what is dominant.

Wangui’s physical appearance continued to change after she arrived in the city. People in the neighbourhood began to wonder why a “boy” was wearing dresses and skirts. As a result of her growing dissatisfaction with her body, she attempted suicide twice more. It wasn’t until 2012 that she decided to finally confide in her sister, and then their mother, both of whom were extremely supportive. Wangui also changed her name to John Karanja at this point, hoping to make it official as soon as possible.

According to the task force report, intersex is not a new phenomenon or concept. While the existence of intersex people has long been recognised in Kenya, talking about sex is frowned upon, and even mentioning the more unusual sex statuses such as intersex is still unthinkable. As a result, most communities either lacked proper names to describe them or used euphemisms to refer to them. These terms are rarely used in public discourse.

Robert Edgerton, an American anthropologist, conducted research on the cultural beliefs and perspectives on intersex people among the Pokot in 1964. According to the study, an intersex child was viewed as an unfortunate occurrence and a freak, with some members of the community stating that if they had such a child, they would kill it. Others saw the killing of intersex children as a cultural and religious obligation.

Retrogressive beliefs continue to endanger intersex children and cases of infanticide (the intentional killing of children under the age of twelve months) continue to be reported in some places, such as Western Kenya, a crime under Kenyan law.

Because of a history of shame and stigma, parents are coerced into subjecting their intersex children to unnecessary surgical procedures in order to “normalise” them and make them fit into binary stereotypes. Jedidah Wakonyo Waruhiu, a former commissioner at the Kenya National Commission on Human Rights (KNCHR) and former member of the Intersex Persons Taskforce, believes that the right to health of intersex people should be guaranteed before birth.

According to Jedidah, “assigning a gender to intersex children causes problems in their natural biological and social lives.” “It becomes more problematic when parents force their children to undergo gender normalising surgeries, even if the sex development disorders do not pose a health risk,” she adds.

This is what happened to *Zuri, who was forced by her family to have surgery at the age of 16. Zuri, now in her 30s, had not realised her body was different until she was eight years old. Her parents were aware of her intersex status from birth and even had an endocrinologist (a doctor who specialises in diagnosing and treating hormone-related diseases and conditions) confirm it. Despite the ambiguity, they chose to raise Zuri as a girl and stuck to their decision, even as male characteristics emerged over time.

The doctor advised them not to operate on Zuri because there was no danger to her health. Ignoring the doctor’s advice, Zuri was subjected to the surgery that would transform her into the daughter they had always wanted, assuming her health was not jeopardised.

What followed was hormone replacement therapy and chronic depression. Her academic performance suffered as a result, and she attempted suicide on several occasions. “The mental anguish and physical problems I’ve had as a result will most likely never be resolved,” she says. Sadly, being intersex comes with stigma. Many times, Zuri, a freelance web developer and graphic designer, has potential clients cancel their projects based solely on the sound of her voice. “Traditional 9 to 5 jobs don’t work for me because I don’t “fit” in hierarchical structures,” Zuri explains.

Ignoring the doctor’s advice, Zuri was subjected to the surgery that would transform her into the daughter they had always wanted, assuming her health was not jeopardised.

Kenya became the first country in the world to count intersex people as a stand-alone group during the 2019 Population and Housing Census. Conversations about intersex people were rare on public platforms prior to 2007, and have been gradually peaking since then. The first case involving the rights of people with intersex conditions in Kenya was presented in court that year, prompting an increase in media coverage.

Unlike Karanja, Zuri has never had trouble obtaining official documents because her birth certificate and all related documents show that she is female. She has never been denied services.

Karanja, on the other hand, has faced a slew of difficulties. In 2012, he went to Milimani Law Courts to have his name legally changed so that he could change his academic records and resume school. He was a bright student who hoped to return to school, either all-male or mixed, where his gender ambiguity would not be an issue. Karanja and his family requested that the Kenya National Examinations Council (KNEC) change the name on his primary school examination records because no school would admit him. It was difficult to follow up on the case because they couldn’t afford a lawyer.

Karanja met a benefactor during this time who assisted him with the medical process of testing and, later, surgery. Between 2013 and 2017, he underwent four successful surgeries. In 2015, the benefactor helped him enrol in an all-boys school in Kisumu. Except for the principal, no one knew he was intersex. Karanja, however, was unable to take his national examination at that school because his official name remained “Dorcas Wangui.” He enrolled in a mixed school to take his final exam, where he had to present an affidavit proving his gender identity.

Karanja believes that if he had been identified as intersex at birth, access to basic human rights such as education would be the reality rather than a pipe dream. He is unable to enrol for higher education because his image and the names on his documents are contradictory. Years later, he is still attempting to persuade the Kenya National Examinations Council to change the name. According to the task force report, the majority of intersex people of school-going age have limited access to education, with only about 10 per cent completing tertiary education.

Level of education in intersex persons

The Taskforce Report made a key recommendation that the relevant agencies expedite the provision of birth certificates, identification documents, passports, and other official personal documentation that include provisions for the intersex (I) marker. This would be accomplished through the amendment of the Births and Deaths Registration Act (Cap. 149), the Registration of Persons Act (Cap. 107), the Interpretation of General Provisions Act (Cap. 2), the Kenya Citizenship and Immigration Act, (Cap 172), and the Children Act, 2001.

The Kenyan government established an Intersex Persons Implementation Coordination Committee (IPICC) in 2019 with the mandate of assisting the government to implement the recommendations of the Intersex Persons Taskforce Report. According to Veronica Mwangi, IPICC’s Head of Secretariat, the IPICC is in the process of developing a database for intersex people that will ensure centralized data for all intersex children and adults in Kenya to help the government make decisions.

Kenya became the first country in the world to count intersex people as a stand-alone group during the 2019 Population and Housing Census.

Veronica points out that Kenya made big strides by becoming the first country globally to count intersex people as a stand-alone group in the 2019 Population and Housing Census. “This has paved the way for the inclusion of an intersex sex marker in key government systems such as Chanjo (the COVID-19 vaccination portal), the Kenya National Commission on Human Rights (KNCHR) complaints management system and the Independent Policing Oversight Authority (IPOA),” she says.

In 2021, the secretariat was joined by a member from the civil registration services, a move that is critical in ensuring children born intersex have a right to a name and that name change services are simplified. Veronica also mentions that IPICC has been collaborating with the Kenya Law Reform Commission, the Office of the Attorney General and legal practitioners to develop a comprehensive law amendment that will address the concerns of intersex people. Karanja is one of 1,524 intersex people counted in the 2019 census, out of a total population of approximately 47.6 million. The census was conducted from 24 to 31 August 2019, with a follow-up exercise on 1 and 2 September to cover those who were not counted during the seven-day period.

Karanja is one of 1,524 intersex people counted in the 2019 census, out of a total population of approximately 47.6 million. The census was conducted from 24 to 31 August 2019, with a follow-up exercise on 1 and 2 September to cover those who were not counted during the seven-day period.

A year earlier, the Intersex Taskforce had published a report in which they estimated that the population of intersex persons in Kenya was 779,414. The taskforce had conducted a field survey in each of the 47 counties from June to October 2018. To supplement the research, data collected by the Kenya National Commission on Human Rights between October 2016 and April 2017, as well as data from various state and non-state institutions, were used. This was Kenya’s first survey specifically targeting intersex people.

The discrepancy in the intersex data collected is astounding. According to former commissioner Jedidah Waruhiu, a follow-up by the KNCHR after the census revealed that while the enumerators had received intersex training, certain cultural factors came into play during the data collection process. For example, the mostly-young enumerators felt awkward asking elderly people gender and sex-related questions. Similarly, those who were not explicitly asked the gender marker question found it difficult to raise the issue, fearing that the revelation would stigmatise them in the community. “Many families were not comfortable answering the sex question as the majority of enumerators were locals in the areas where they were collecting data,” says Jedidah.

In other cases, the enumerators would simply look at a person and, without asking a question, indicate on the form the gender of the person they were interviewing based on their outward appearance, such as mode of dress. This was done so that they could quickly finish the questionnaire and move on to the next person. As a result, many intersex people were left out of the count.

Other than the census, the Kenya National Bureau of Statistics (KNBS) has not included intersex persons in any other of its reports. Despite accounting for less than 1 per cent of the population, intersex persons are important contributors to the economic growth of the country, according to the KNBS research. According to the census report, at least 41 per cent of intersex people were in the labour force.

Despite global progress in recognising intersex peoples’ rights, the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) do not include intersex people. SDG 5 addresses gender equality, but the emphasis is on women and girls. However, an indirect reference is made to SDG 10, which deals with reducing inequalities within and between countries. By 2030, one of the SDG targets is to empower and promote the social, economic, and political inclusion of all people, regardless of age, gender, disability, race, ethnicity, origin, religion, or economic or other status.

This also applies to SDG 16, which aims to promote “peaceful and inclusive societies for sustainable development, provide access to justice for all, and build effective, accountable, and inclusive institutions at all levels.” SDG 16 includes goals such as “providing legal identity for all, including birth registration,” and “promoting and enforcing non-discriminatory laws and policies for sustainable development.”

Despite global progress in recognising intersex peoples’ rights, the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) do not include intersex people.

While the SDGs do not include direct targets for intersex people, policymakers and stakeholders in participating states have a responsibility to provide them with equal opportunities because they are bound by international and regional legislative and human rights frameworks.

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), for example, recognises all people’s inherent dignity and worth, stating unequivocally that “all human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights”. Another important framework is the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), which guarantees the right to self-determination and the enjoyment of all other ICESCR rights to all without regard to gender, birth, or other status.

In Kenya, granting intersex people the right to documentation, which unlocks many of their rights and freedoms, is key to enabling intersex people to contribute to the economy.

Richard Muasya, an intersex person, filed a case in court in 2010 alleging violation of his constitutional rights. Muasya had been charged with the capital offence of robbery with violence a few years before, arrested, and imprisoned in Kitui. Following the discovery of Muasya’s intersex status during a routine physical search, the Kitui Magistrates Court ordered that he be remanded in isolation at the Kitui Police Station pending trial.

Muasya was later convicted, sentenced to death, and transferred to Kamiti Maximum Prison, a male-only prison for death row convicts. Muasya was initially forced to share cells and facilities with male inmates, but was later held in solitary confinement. Because of his condition, he was allegedly subjected to invasive body searches, mockery, and abuse while in prison.

Muasya argued in court that he should have been detained in a separate facility with specially trained staff rather than being placed in a male prison. The court acknowledged that the petitioner’s situation was unique and had not been anticipated by the legislature, but determined that creating a prison specifically for him would be impractical.

In Kenya, granting intersex people the right to documentation, which unlocks many of their rights and freedoms, is key to enabling intersex people to contribute to the economy.

The court ruled that neither the Prisons Act nor the Prisons Rules discriminated against intersex people. It dismissed Muasya’s claim that he was unconstitutionally detained in the police station while his trial was pending, and ruled that the petitioner’s social stigma was not a legal issue. Further, the three-judge panel ruled that there was no empirical data that could lead the court to conclude that intersex people require recognition. The court, however, awarded Muasya KSh500,000 in compensation for the inhuman and degrading treatment he endured.

Regardless, the Prisons Act did not (and still does not) specify where intersex people should be detained.

Advocacy for issues affecting intersex people was low-key at the time. Kenya was undergoing constitutional reform at the time Muasya’s case was dismissed. According to former KHRC commissioner Jedidah Waruhiu, this was a missed opportunity to incorporate intersex issues into the constitution.

Three years later, a petition for Baby A, an intersex baby born at Kenyatta National Hospital, was filed in court. The hospital included a question mark in the column for indicating the person’s gender in the birth notification document. The baby’s mother claimed that the use of a question mark to indicate the baby’s gender was a violation of the child’s rights to legal recognition, dignity, and freedom from inhuman and degrading treatment. Furthermore, the petitioner claimed that the failure of legislation such as the Registration of Births and Deaths Act to recognize children with intersex conditions violated various children’s rights guaranteed by the constitution as well as various international human rights treaties.

In Kenya, only a handful of laws have been changed to accommodate intersex people. According to the 2014 Persons Deprived of Liberty Act, while a body search of any person must be carried out by a person of the same sex, an intersex person has the right to choose the sex of the person conducting the search.

The Registration of Persons (Amendment) Bill, 2019 is currently pending in the Senate. Once approved, the Intersex sex marker will be concretised as a third sex marker in law. Being intersex is a gender marker, just like being male or female, and is usually assigned at birth based on sex characteristics. Being intersex is frequently misunderstood as a description of one’s sexual orientation or gender identity (the personal sense of one’s own gender, which may differ from the assigned sex in some cases). It is frequently lumped into the LGBTQIA category, and as a result, people are dismissive of intersex people’s plight.

Being intersex is a gender marker, just like being male or female, and is usually assigned at birth based on sex characteristics. Being intersex is frequently misunderstood as a description of one’s sexual orientation or gender identity (the personal sense of one’s own gender, which may differ from the assigned sex in some cases). It is frequently lumped into the LGBTQIA category, and as a result, people are dismissive of intersex people’s plight.

Granted, much of the societal apathy stems from how the media, both local and international, covers stories about intersex people. For a long time, they were referred to as “hermaphrodites”, implying that they are both fully male and fully female. That is not only deceptive but also stigmatising. While they are now referred to as “intersex people”, reports about them are still sensationalised, which is usually a ploy to attract more readers.

When ratings and readership come first, no matter how accurate the information, the news often becomes a mere source of entertainment. It cannot be overstated how damaging sensationalisation of such issues is to society. People’s perceptions of even the most mundane things are shaped by the news. Reports on intersex people, on the other hand, must be approached with the utmost professionalism and respect if we are to change the narrative about them.

Kenya could possibly borrow best practices on reporting from the Australian Human Rights Commission. Their reporting guidelines for people born with sex differences advise journalists to always begin by asking the interviewee about their preferred terms or descriptors, and to avoid making assumptions about the terms a person may use.

It is important to note that unless an intersex person has volunteered that information, asking them questions about their bodies or genitals is inappropriate. Additionally, the interviewer should not mix up Intersex issues with sexual orientation, gender identity, or LGBTQI identities.

When ratings and readership come first, no matter how accurate the information, the news often becomes a mere source of entertainment.

Not to be overlooked is how a lack of data contributes to a fair share of misinformation and stigmatisation of intersex people, both past and present. In the absence of hard evidence on intersex people, retrogressive cultural beliefs that lead to infanticide or abandonment of intersex children who are perceived to be a curse, as well as misinterpretations of religious canons, are used to frame the narrative.

Intersex people face discrimination at school, work, and in social settings as a result of misinformation and stigma. This has an impact economic wellbeing due to a lack of job opportunities and, in some cases, a lack of education. Overall, the impact on their mental health is immeasurable from a young age.

Greater intentionality is required to make intersex people more visible and heard, which requires continuous data collection and their inclusion in all country statistics. Hopefully, this will lead to more accurate and more nuanced discussions about intersex people.

Jedidah contends that introducing the Intersex “I” marker will allow medical professionals and parents to follow up on children since birth, raise them as intersex, and biologically monitor them. “This fixing of male or female is what is causing problems for the children as they grow in their natural biological life, as well as in their social life,” she adds.

There is an urgent need to educate healthcare workers across the country about the needs and rights of intersex people. This awareness should be achieved both during and after training. According to Dr Laigong, the Ministry of Health should provide additional assistance by providing diagnostic equipment, lab support, and social amenities. However, he observes that progress in sensitising medical practitioners is being made. “Right now, the University of Nairobi has a fellowship programme to train paediatricians in paediatric endocrinology,” he explains.

Veronica Mwangi observes that while the government has set up the Intersex Persons Implementation Coordination Committee, no funds have been allocated to the secretariat to support intersex people’s work or programming. As a result, there is a lack of public awareness across the country about who intersex people are and the importance of protecting them. Donor support is also difficult to come by. “Some donors are hesitant to support intersex person programmes on their own,” she adds.

The world is gradually realising that referring to intersex people as hermaphrodites is derogatory. Intersex people’s human rights violations extend beyond barriers to healthcare and employment. Gender-based violence, educational access, and land rights are all issues that must be addressed.

During antenatal care, expectant mothers should be tested for intersex genetic conditions, according to Jedidah. This way, the doctors and parents of an intersex baby can ensure that the necessary treatment and documentation is provided from the start. Furthermore, if the gender of the baby is unknown, registration bureaus should add an ‘I’ marker to avoid guessing the sex.

The world is gradually realising that referring to intersex people as hermaphrodites is derogatory.

Karanja is still determined to attend university and pursue a degree in information technology (IT). However, before this can happen, his Kenya National Examinations Council certificate must show the name John Karanja rather than Dorcas Wangui. He recently completed a certificate course in Graphic Design and is looking for work in the field.

Zuri, on the other hand, is still undecided about changing her marker in the future. “It shouldn’t be up to an oppressed group to constantly demonstrate their humanity,” she says. “Regardless of the circumstances, we are all deserving of equal rights under the law.”

–

This article was produced with support from the Africa Women’s Journalism Project (AWJP) in partnership with Article 19, Meedan and the International Center for Journalists (ICFJ).

Based on the MOH daily cumulative number of vaccines administered, Kenya is on course to have 10 million vaccines administered by Christmas, based on the predictive AutoRegressive Integrated Moving Average (ARIMA( 5,2,1)) model.

Published

on

By

During his eighth and last State of the Nation address on 30 November 2021, Uhuru Kenyatta reminded the nation of his pledge to have at least 10 million Kenyans vaccinated by Christmas. With just 25 days to go, the president urged Kenyans to get vaccinated to meet and surpass that target.

On the day of the president’s address, just 7,175,590 doses of the 13,909,670 received in the country had been administered.

The pressure to vaccinate Kenyans has been increasing. Data shared by the Ministry of Health in late November indicated that less than 10 per cent of the targeted population was fully vaccinated and about 15 per cent had received at least one of the COVID-19 vaccine doses.

Just nine days before the president encouraged Kenyans to get their COVID jabs, Cabinet Secretary for Health, Mutahi Kagwe announced some tough measures. He said that Kenyans will be required to show proof of vaccination when boarding domestic flights, trains and buses, and while travelling from one region to another.

“Everybody seeking in-person government services should be fully vaccinated and proof of vaccination availed by December 21st 2021,” he said. “Such service will include but not limited to KRA services, education, immigration services, hospital and prison visitation, NTSA and Port services among others.”

The announcement sparked much debate among the public. Human rights defenders argued that the measures violated freedom of choice and threatened to deny basic services to citizens. Some taxpayers even joked about not paying their taxes since if they were unvaccinated, they would not be receiving government services.

Business owners, especially in the tourism sector, criticised the potential negative impact of these pronouncements on their businesses which experience a boom during the Christmas holidays.

But in the week following this announcement, the number of doses administered daily increased to over 100,000, except on the Saturday and Sunday. This is a significant rise. If we take data beginning on 28 September 2021, when MOH began to consistently upload the status reports, the average number of vaccines administered on a daily basis since that date was 52,796.

The vaccination process has been highly dependent on the availability of vaccines, with more than half being donations from higher-income countries like the US, UK, Denmark, Poland, France, etc.

Where the dates have been disclosed, the duration to expiry of the donated batches was between 25 and 136 days. While the Johnson & Johnson batch that the government of Kenya had received on 3 September 2021, just before it last reported the expiry date of various vaccine batches, had 635 days to expiry.

It is not reported whether there were any vaccines that were discarded because they had expired.

Kenya had received 13,909,670 vaccines by 30 November 2021. The challenge is to match uptake with the now increased availability of vaccines. More than half of these vaccines are yet to be administered.

So, how likely is it that the government will have every adult Kenyan vaccinated by 21 December 2021 to avoid the consequences announced by CS Kagwe? Or is President Kenyatta’s Christmas pledge more realistic?

Based on the MOH daily cumulative number of vaccines administered, Kenya is on course to have 10 million vaccines administered by Christmas, based on the predictive AutoRegressive Integrated Moving Average (ARIMA) model.

But this forecast will become reality if more Kenyans are persuaded to take the time to visit their nearest medical facility which according to the President is now stocked with the vaccine doses.

More realistically, about 9 million doses could be administered by Christmas if all factors remain constant.

The cumulative number of vaccines administered is non-stationary, meaning that it has a time-dependent structure and does not have constant variance over time. This can be attributed to pattern changes based on the availability of COVID-19 vaccine doses in the country and also due to various efforts undertaken by the ministry at different times.

It is clear, however, that the uptake of the doses has now become steady. But the uptake is not increasing at the same rate as the vaccines are becoming available. This could be because of ineffective communication to the public. Also, there may be vaccination apathy following the long waits for sufficient vaccines, the long queues once they become available and visits to medical facilities only to find no vaccine. I made one such visit which was disappointing.

Worthy of note is that in August the government issued its first vaccine mandate to all public servants who were compelled to get COVID jabs or face disciplinary action.

Now, over 95 per cent of health workers and teachers are fully vaccinated. The new mandate widened the scope to the general population, including millions of jobless Kenyans, and seems to be bearing fruit already.

The prediction above is based on the kind of data the ministry of health has released. The MOH Twitter page and website have been the main avenues through which vaccination progress has been communicated.

Looking at the vaccination data, one gets a sense of how the data aspect of this pandemic has been a case of “building a plane while you fly it”. This can be seen in the way data is released for public use.

Data is first shared in the form of images on twitter and PDF documents are then uploaded on the MOH website.

Let us drill down to illustrate some problems by focusing on 14 July 2021.

Additionally, the number of total daily vaccinations in the status reports uploaded on the MOH website differs with what is in the Humanitarian Data Exchange (HDX), HUMDATA, an open platform for sharing data across organisations which relies on figures that are verifiable based on official public sources including Our World in Data (OWID) who in turn extract data from the updates from the MOH twitter timeline as well as on the website.

Another major issue for anyone seeking to explore Kenya’s vaccination data is missing data.

Dataset such as HUMDATA and OWID had data scraped from the MOH twitter updates initially. We had to combine data from the HUMDATA dataset and MOH status reports together to reduce the amount of missing data. However some figures recorded by Humdata were a day ahead compared to the figures in the available status reports presented on the MOH website.

The level of readiness in terms of how to capture and manage the data is questionable. The status reports shared had not captured or anticipated the assortment and diversity of the vaccines Kenya would receive over time. Several elements (variables) are introduced at different times. This makes any automated technique of extracting the data extremely difficult and time-consuming. For example, up until 1 July, the reports had “Cumulative persons vaccinated to date”. But this was changed to “Total vaccinations” to cater for those who were receiving their second doses of the AstraZeneca vaccination which began on 28 May 2021. Later it emerged that just a single dose of Johnson & Johnson would amount to full vaccination status so official data was changed from Dose 1 and Dose 2 to partially and fully vaccinated persons.

Gender was another variable that evolved with time. Initially genders were badged male, female and “other”. This was later changed to “intersex”, and “transgender” was subsequently added.

These discrepancies, in addition to the data provided in PDF forms, make it extremely difficult and time consuming for experts to explore the data and for the public to monitor the accountability and transparency of the vaccine uptake.

–

This OUTBREAK story was supported by Code for Africa’s WanaData program as part of the Data4COVID19 Africa Challenge hosted by l’Agence française de développement (AFD), Expertise France, and The GovLab

COVID-19 has shown that there is a need for revolutionary thinking within the education sector if all children are to get a chance of an education.

Published

on

By

The Ministry of Education in Kenya has continued to push for 100 per cent transition of pupils who sit for the Kenya Certificate of Primary Education (KCPE) examinations in order to ensure that every child gets the full benefits of a secondary education.

Secondary school is the bridge between primary level education and tertiary education whose benefits go beyond attaining a formal education. For instance, secondary education contributes to the reduction of HIV infection among girls, as they are able to delay becoming sexually active and avoid early marriages. Access to a secondary school education also reduces poverty among girls and enhances their chances of employment. Secondary education also benefits the whole society as girls, and the youth in general, spend more time in school, and are therefore less likely to become involved in violence, either as perpetrators or as victims of crime.

Moreover, evidence shows that a secondary education leads to a decline in socio-economic inequality between girls and boys, with secondary education having the most effect on bridging the gap. Furthermore, evidence suggests that children of educated mothers are more likely to progress and complete school than those children whose mothers are not educated. Overall, a secondary education levels the field of opportunity for young people and increases their chances of earning higher incomes and thereby attaining a higher standard of living.

Data from the Kenya National Bureau of Statistics shows that between 2016 to 2020 secondary school enrolment by class and sex grew by 8 per cent to about 3,520,000, out of which 50.3 per cent were girls. This increase was attributed to the government’s policy of ensuring 100 per cent transition from primary to secondary school. Looking at the 2020 school year, following the COVID-19 pandemic, Kenya’s total secondary school enrolment decreased from 3.5 million in March 2020 to 3.3 million in March 2021, a 5.7 per cent drop as schools reopened. Moreover, out of those enrolled in March 2020, approximately 233,300 students did not return to school to resume learning when schools reopened in March 2021, representing 6.6 per cent of the students enrolled in March 2020. The number of secondary schools that were able to reopen increased by 0.4 per cent.

While between 2016 and 2020, there was an increase in the number of pupils transitioning to secondary school, the decrease in enrolment between March 2020 and March 2021 prompted the Ministry of Education to reach out to parents across the country in a bid to ensure that all children returned to school. The drive faced challenges including poverty, poor parental attitudes towards education and ad hoc policy implementation.

Evidence shows that a secondary education leads to a decline in socio-economic inequality between girls and boys.

But by far the most common and most significant challenge to the push for 100 per cent transition to secondary school has been poverty. Many parents say that a lack of resources hinders them from sending their children to secondary school, a challenge that has been exacerbated by the impact of COVID-19 on household incomes across the county. Parental attitudes where for one reason or another parents resist sending their children to school also pose a challenge. Calls for parents’ cooperation from the Cabinet Secretary for Education echo my reflections in a 2018 article where I observed that “bottom-up strategies” may be useful in creating the groundswell for the transition push. This would help avoid the implementation of haphazard policies such as sending government officials around the counties to “drive children back to school”. If parents work with both the national and county governments, they will create a sustained push to ensure that students not only make a transition to the first year of secondary school but that they also stay in school.

In addition to stimulating an attitude shift in parents, particularly towards their children’s education, it is important that the Ministry of Education, in collaboration with Non-Governmental organizations, develop programmes that can empower the parents financially to keep their children in school. The Advanced Learning Outcomes project (ALOT Change), a community-based initiative by the African Population and Health Research Center (APHRC), has been instrumental in working with parents in Nairobi’s informal settlements so that they can better understand their own roles in the education of their children.

By far the most common and most significant challenge to the push for 100 per cent transition to secondary school has been poverty.

Education stakeholders in both the public and private sector need to work in close partnership to seek better ways of providing scholarships for those children who are in need of school fees support. Through A LOT Change, APHRC has provided subsidies to pupils transitioning to secondary school. The US$ 113 subsidy has been instrumental in decreasing the financial burden of parents, as they are able to purchase books, school uniforms, and other materials required for school. The lessons learned from such programmes can be adopted and scaled up by both the public and private sectors in order to provide relief to parents facing financial challenges.

Some of the students who were “driven back” to the first year of secondary school had to go to school in their primary school uniform. Might it also be time for the education system in Kenya to reconsider the issue of school uniforms? This could also contribute in a small way to reducing the financial burden for parents. Moreover, COVID-19 has shown that there is a need for revolutionary thinking within the education sector if all children are to get a chance an education. The government therefore needs to ensure that schools are better able to take advantage of emerging technologies such as EdTech by, for instance, improving school infrastructure (including computer labs) and access to electricity. This would enable schools to provide both virtual and in-classroom teaching and thus ensure that students get the best of blended learning, linking the finest tenets of in-person and virtual learning.

Why are Ethiopians Dying in Isaias’ War?

Soko Mjinga: The Shamba System

GMOs: Entrenching Kenya’s Food Insecurity

Land Governance Priorities for the New Administration in Kenya

Life on the Day of a Coup: Keeping Up With the Koupdashians

Burning Ambition: Education, Arson and Learning Justice in Kenya

Queen Elizabeth II and the Weight of History

Africa in the 21st Century: From Pawn to a Significant Player

Copyright © 2017-2022 The Elephant. All Rights Reserved.